by Brett Rutherford

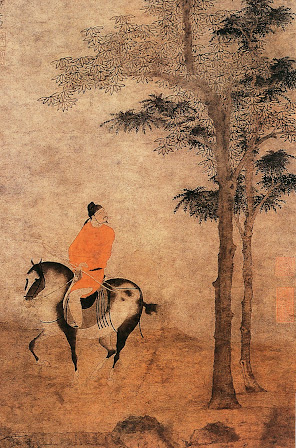

Emperor Li

Yu (937 – 978 CE)

Now I am dead.

There is no other way

to write this poem

except backwards.

Because Taizong

resented my last poems

(who would not yearn

for what he has lost?) —

because I am said to be

all things considered,

a better poet.

Because I cared less

with each day’s passing,

wife torn from me,

a weeping shell of herself,

since she was raped

by the Song Emperor.

Because I will not address

that personage correctly,

because I am now called,

not former Emperor, not King,

not as Li Congjia, the name

my father gave me,

the name to which

all people and foreigners

knelt and kow-towed,

but by an epithet:

Marquis of Wei Wing

(Lord of Edicts Disobeyed).

Now I am dead,

because my generals came

with warlike strategy,

and I dismissed them,

preferring my evenings

in the Poets’ Pavilion,

with painters and artists

who fled to me from

every other kingdom.

Now I am dead,

because my captive brother

summoned, implored,

my travel to Song’s capital,

and I went not. Instead

I sent poems and art,

the best ambassadors

of peace and accord.

Now I am dead.

No armor did I don,

no chariot ascend

when the invaders came.

I was in the temple,

composing a poem,

surrounded by monks,

incense, and prayer wheels,

when they broke in

and seized me. Where

was the magic, then?

Now I am dead,

because wise counselors

wanted me strict, cruel

and cunning, like those

who raced to crush

our borders. Refusing,

I sent them home.

Some killed themselves

in honor’s name.

It was I who killed them!

Now I am dead,

who tried to have

one woman as wife,

and her younger sister, too.

As for the two women,

one died, and then I married

the other. Is that not honorable?

Did I not carve,

with my own hand

two thousand characters

on the Empress’s tombstone?

Those who forbade my love,

and my second marriage,

I sent home to their villages

to live until their beards

touched ground.

Now their ghosts haunt me.

Now I am dead,

because I drank a cup,

an overflowing cup

of heart-warm wine,

best of the southern

vineyards, I was told.

Because my dishonored wife

put her pale hand

upon the celadon vessel

to taste it first,

and a soldier pushed

her aside and said,

“This wine is for one,

from the Emperor’s table.

The Marquis only must drink.”

“I am not thirsty,” I said.

“The Marquis must drink.

I must say at his table

that you have tasted it,

and in full proof of pleasure,

have drained it to the dregs.”

Now I am dead,

because the willows of home

have wept two years for me;

twice have I left unswept

the tombs of my fathers;

twice have I failed to lift

up in the dead’s honor

a flagon of chrysanthemum;

and twice has the Lunar Year

come and gone in a place

that no longer has my name.

Peace be to you, Song Emperor,

and to all peoples. I am still

King of leaves and petals, Lord

of moonlight and sudden breezes.

Who will they read

a thousand years from now?

Now I —