by Brett Rutherford

Adapted from Lantingji Xu, “Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion” by Wang Xizhi (303-361 CE, Jin Dynasty)

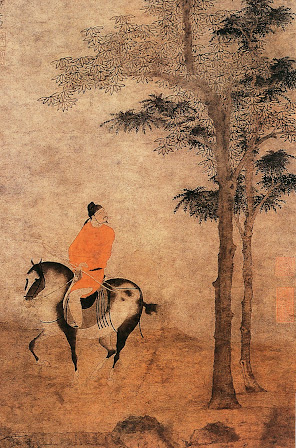

In fourth century China, the Jin emperor presided over a picnic of poets in which all sat alongside a gentle stream. Wine cups were placed on large leaves and dropped into the stream. Any time a wine cup came within reach of a poet, he was required to take it up and drink it, and/or write a poem on the spot. My friend Ping Geng obtained for me a ceramic replica of one of the little cups used at this famous poetry gathering. The event yielded an anthology and here is my adaptation of the dedicatory poem. The artwork depicts the poets idling along the stream-bank.

The great Jin rules at the world’s center

(may it always be so), and this late spring,

in the ninth year of the Yonghe Emperor

we have gathered at the Orchid Pavilion,

in the cool north of Kauiji Mountain

for the ritual of purification, as always

the Literati gather, ink-pot and brush

as ready as a bannerman’s weapon.

Mistake not the power of these seated men.

We have climbed the steep hills

to reach this mountain slope. The woods

are dense with shadowing pines.

The slender bamboo is emerging

and the flowing stream has swollen

with the rush of melting snow

into an artificial rivulet that bends

and turns across a levelled field

where we spread out in groups

so that each poet’s arm can reach

to touch the limpid waters

on which a broad leaf boat

carries an oblong wine-cup.

If one such vessel comes your way

you are compelled to take it,

if not, you must write a poem.

If excellent, the emperor applauds;

if not, the waters carry it off.

Although no music wafts

among the pine trees, winds

at work on fervent blossoms

and the sweet harmonies of words

suffice to make us happy. Hearts

rise in a bell-symphony of joy.

The sky is free of clouds.

The air is fresh, no hint of smoke.

The breeze is moderate and cool.

Above us, hidden in blue

a billion stars burn ever on.

Among us all, our poems are few,

Although they number tens

of thousands by now. Our eyes

harvest the landscape for images.

Too quick a lifetime passes

when one is among friends,

not years enough! Not years Enough!

We have each our own way with words,

our chambers and all the things in them.

What one collects, another scorns,

Yet out of such diversity there comes

the pleasures and satisfactions

with which we regale one another.

How quickly, alas, this all may pass’

as we grown old, our young desires

seem weary or over-sated;

What once we trafficked in

seems shallow now. We call

the auctioneer to clear things out.

And trailing ever behind us,

the unacknowledged guest,

is grief, its shadow ever-growing.

Long life, short life,

the better lived, the sooner

it seems to come to calamity.

Alas, the ancients knew best:

The only two ultimate things

are the birth that brought you

And the death that takes you away.

Alas that it must be so! Far back

into the ancient works, the same lament.

It saddens me that the worthy dead

came up with no answer for me.

I cannot express how sad this is.

It is absurd to say that death

makes all life meaningless.

Look! One more leaf has fallen!

Which one? Which one? Oh who can tell?

To live long is surely better

than to have scarcely lived at all,

To read and weep, one hand

unrolling the scroll, the other

outlining the share of each character:

Is this not how one lives

in more than one lifetime

inside the minds of the departed?

And just as we read them,

some future reader

will stumble upon these words

And say, “That poet. I think

I know him. Our minds are one.

I might have been him, he, me.

How many poets are here today?

How many brushes at work,

how many completed verses?

Oh, gather them up? All of them!

Let he who made the rivulet

on which the wine cups float,

to carry gently downward

all of our torments and doubts

Into the far-off river, touched

by swallows and dragonflies,

into the great sea of eternity.