The Cannibal Hymn is at least 4,300 years old. It is found in Egyptian Pyramids, and also occurs as a "coffin text." It was so alarming and primitive that the Egyptians eventually stopped making copies of it. It is one of the masterpieces of ancient literature. Here is an abridged, modern adaptation the era of King Donald. (2018 slight revision).

Warming, the weather turns terrible.

The stars frown.

Fracked bones of the earth tremble.

The coal mines are empty and dark

at seeing the Donald rising,

a god of inherited fortune

who feeds on the flesh of his mothers.

Though Donald is Lord of Wisdom, bigly,

his mother does not know his name.

She meekly calls him The Tiny One,

The Giant-Insane-Baby Who Eats the Sky.

Donald’s glory is in the clouds, bigly,

his large hands span the horizon

like his realtor father before him,

though his son, Jared,

is mightier than he.

Donald’s tweets are behind him.

His party, his Dark-of-Water are at his feet.

Jesus and Mammon are over him,

the eyebrow-serpents are on his brow,

the Donald’s guiding over-comb

protects his forehead,

each hair alert for enemies

to add to the death-list.

His neck is there,

not to be moved from his mighty Trunk,

nor shall he arise from his golf cart

except to smite bad people, bad.

His mighty implement is not a mushroom;

yea, bigger than a Behemoth's

is his engorgement.

Donald is the Bull of the Sky;

flag-waving, he alternate-facts

his enemies into submission.

He lives on the past:

without reading its books he

devours its innards.

Everything he does, he does firstly.

He swallows even scientists

without acquiring knowledge;

their magic counts as nothing.

Donald himself suffices.

He assembles his cabinet, then fires them.

Assembles more, and eats them.

Beware the field of spit-out ministers!

Donald appears as the Great One,

shoving aside the foreigners,

yea even Montenegro’s leader.

He calls on tribute lands for tithes,

withholding his hands and mighty arms

on account of less than two percent.

He sits with his back to the Potomac.

He needs no Congress for his advisor

since Him-Who-Is-Not-Be-Named,

the faraway Tsar advises him

on this day of drone-and-missile-sending.

Donald is the Lord of Offerings.

His coffers swell, his tax returns

known only to the gods below.

His meat and his ketchup suffice him;

no foreign chef does he require.

At night he eats his enemies

and sends out tweeted warnings

that the pundits and journals tremble.

His thoughts are like falcons, bigly.

It is “Bring-Back-the-Slave-To-Service” who is Sessions

who lassoes them for Donald.

It is “Snake-Even-Worse-Than-Donald”, the Pence, who guards and keeps the Congress fattened for him.

It is “She-As-Dumb-As-Willows”, named DeVos,

whose job is to keep them meek and stupid.

It is Ryan, slayer of Big Government,

demolisher of Bureaus,

who cuts the throats of the victims, singing,

McConnell the one who will extract the innards.

Conway will cut them up for Donald,

and Sanders the messenger whom Donald sends forth

to say the Yea-That-Is-Nay daily.

His consort Melania, and Ivanka,

darkly-beloved daughter, who cut them up

and pour spice into the Donald’s dinner-pot.

Bigly, the meals, with ketchup.

The ones who serve in Congress,

yea, even the Senate and the House,

from their heights they serve Donald.

The uninsured are butchered, the unborn

one and all are guaranteed to his platter.

Donald eats everything:

athletes for breakfast,

businessmen for his business-man’s lunch,

children for dinner with alt-spice and pepper.

Veterans and seniors are burned as incense.

A cauldron of women for a late-night pussy-grab.

Donald has filled the sky, and is the sky.

He crowns himself with the Pope’s mitre,

the crown of many Kings. He dreams

of Jared, Ivanka as Tsar and Tsarina

of Russo-Europe, the coming empire.

He has swallowed the Red States.

Though he does not like their savor,

He will devour the Blue.

With the help of his Dark-of-Water,

he will march against the Urals

and snap the necks of the Asian warlords.

He has swallowed all knowledge

and never once passed gas or turdling,

so he has forgotten nothing.

His reign will be limitless; he is the sum

of all the enemies he has devoured.

Whomever he likes is good,

whomever he dislikes is loser, Kenyan.

Soon no one will be left unbowed.

The rest will be eaten.

Do-gooders and liberals are helpless before him.

His tower of gold and marble the highest,

himself on top, immortal, beloved

of gods and the blazing stars.

He is forever, and forever, the Donald.

Poems, work in progress, short reviews and random thoughts from an eccentric neoRomantic.

Monday, May 29, 2017

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

Alien Covenant -- A Review

Most of my friends seem to have hated the new film Alien Covenant. It

is director Ridley Scott's follow-on to the baffling Alien "prequel,"

Prometheus, and it fills in many gaps in the narrative.

Friends commented on the stupid actions by the characters being pursued and devoured by the aliens, but they are an underpaid crew ferrying colonists in space, not scientists on exploration, and "first contact" was the last thing they expected.

The film contains serious debates about artificial intelligence/robots and the ethics thereof; the question, from Frankenstein, of whether the creation should have contempt for its physically frail creator; it quotes from Wagner's Ring Cycle both musically and in ideas; it evokes and quotes Milton, and Shelley's "Ozymandias."

Alien Covenant includes a necropolis city it will be impossible to forget, one aspect of which is lifted directly from Arnold Bocklin's painting, "The Isle of the Dead." It plays on twins/doppelgangers. And it advances the Alien story-line continuum with a new agency, many twists of the created turning against the creators. It suggests that species are not kind to one another, and that mutual annihilation might be out there in the stars as well as on earth.

The weak part of the script is that the only intellectual characters are robots, and the humans bumble around, trying to substitute bravery for brains. But that too, is part of the message throughout these films: a safe world is safe for the not-so-bright, too. We don't get close to any of the characters to bond with them the way we did with Sigourney Weaver in Alien/Aliens/Alien3, and that is too bad. It is too easy to forget that the Earth culture of the Alien series, toward which this episode is building, is a dystopia in which free-thinking individuals seem to have been pushed aside in favor of desperate workers who want to obey orders and get their next paycheck. And going into space does not appear to be a plum job.

If you have seen

the previous films and thought about them, you need to see this one

too, and then go home and think about it. And then don't go near

anything even remotely shaped like an egg.

Friends commented on the stupid actions by the characters being pursued and devoured by the aliens, but they are an underpaid crew ferrying colonists in space, not scientists on exploration, and "first contact" was the last thing they expected.

The film contains serious debates about artificial intelligence/robots and the ethics thereof; the question, from Frankenstein, of whether the creation should have contempt for its physically frail creator; it quotes from Wagner's Ring Cycle both musically and in ideas; it evokes and quotes Milton, and Shelley's "Ozymandias."

Alien Covenant includes a necropolis city it will be impossible to forget, one aspect of which is lifted directly from Arnold Bocklin's painting, "The Isle of the Dead." It plays on twins/doppelgangers. And it advances the Alien story-line continuum with a new agency, many twists of the created turning against the creators. It suggests that species are not kind to one another, and that mutual annihilation might be out there in the stars as well as on earth.

The weak part of the script is that the only intellectual characters are robots, and the humans bumble around, trying to substitute bravery for brains. But that too, is part of the message throughout these films: a safe world is safe for the not-so-bright, too. We don't get close to any of the characters to bond with them the way we did with Sigourney Weaver in Alien/Aliens/Alien3, and that is too bad. It is too easy to forget that the Earth culture of the Alien series, toward which this episode is building, is a dystopia in which free-thinking individuals seem to have been pushed aside in favor of desperate workers who want to obey orders and get their next paycheck. And going into space does not appear to be a plum job.

Thursday, May 18, 2017

Against Copyright

The "public domain" is the world's intellectual treasure-house of all

the art, writing and music that has ever been done by humans. It is our

common inheritance and is the sum of what it is to be human -- to have a

direct connection to all who came before. This means that all these

works may be copied, edited, sequeled, adapted into other media, etc. It

is your right to do so. Copyright laws are do not protect a right --

they take a right away for the benefit of publishers and authors,

originally for a limited time. Copyright used to be 28 years, renewable

once if the author or publisher bothered to re-register. Thanks to the

machinations of lawyers protecting Mickey Mouse, U.S. copyrght is now

something like 95 years past the death of the 'creator'. They are

pushing to make these copyrights, in effect, go on forever.

Copyrights extended this way hamper the creativity of those seeking to create derivative works, or even just to quote from or adapt the originals, all for the benefit of people referred to in my circle as "shiftless heirs." People who do no work, collecting royalties into infinity, and prohibiting posterity from creating new work with paying them ransom.

In the case of poetry, I have seen "shiftless heirs" of a dead poet, harboring a fantasy of future wealth, and prohibiting any of the poet's friends from assembling and publishing books of their work. I have seen poets' life work hurled into dumpsters by contemptuous family members. Copyright serves no one when the work has no monetary value -- ironically, poetry, one of the ultimate treasures of any era, is almost always regarded as trash by the contemporary culture around it.

So, for poetry, I stand against copyrights altogether, and encourage poets to place statements on their copyright page, specifying the year in which they wish their work to be in the Public Domain. To hell with the lawyers.

Copyrights extended this way hamper the creativity of those seeking to create derivative works, or even just to quote from or adapt the originals, all for the benefit of people referred to in my circle as "shiftless heirs." People who do no work, collecting royalties into infinity, and prohibiting posterity from creating new work with paying them ransom.

In the case of poetry, I have seen "shiftless heirs" of a dead poet, harboring a fantasy of future wealth, and prohibiting any of the poet's friends from assembling and publishing books of their work. I have seen poets' life work hurled into dumpsters by contemptuous family members. Copyright serves no one when the work has no monetary value -- ironically, poetry, one of the ultimate treasures of any era, is almost always regarded as trash by the contemporary culture around it.

So, for poetry, I stand against copyrights altogether, and encourage poets to place statements on their copyright page, specifying the year in which they wish their work to be in the Public Domain. To hell with the lawyers.

Thursday, May 11, 2017

Four Generations of Rutherfords in the "Book Business"

Runs in the family, even though I was separated from the Rutherfords at age 13.

My great-grandfather John Rutherford came from England to Scottdale, PA, and ran a book and stationery store (other Rutherford siblings had shoe factories, coal mines, banks, and a steam engine factory).

My grandfather took over the "bookstore" and became a newspaper distributor for several counties. Untold numbers of paperboys worked for him, and he sponsored 12 boy scout troops.

Some of the Boy Scout troops had marching bands and they probably bought their instruments at a local store called "Rutherford Studios." It was rumored of the Rutherfords that any of them could pick up any musical instrument and be able to play it within a few months.

One auntie secretly wrote poetry.

The news store was inherited by my Uncle Bill, a grumpy man with an eye-patch who lived above the store. Rutherford News closed forever sometime in the late 1970s.

As a child in Scottdale, I would cut up magazines and rebind them in various ways and sell them to neighbors; I also printed a mimeographed science newsletter and tried to draw comics. By the fifth grade I was writing monster plays and staging them in a local garage, and charging admission to the all the neighborhood kids. People in town said I was just like my grandfather.

And here I am, a curmdugeon, publishing books and picking away at writing and music. Did I have any choice in the matter?

This corner building was the site of Rutherford News. Since it was built around 1880, it was probably always in the family.

My great-grandfather John Rutherford came from England to Scottdale, PA, and ran a book and stationery store (other Rutherford siblings had shoe factories, coal mines, banks, and a steam engine factory).

My grandfather took over the "bookstore" and became a newspaper distributor for several counties. Untold numbers of paperboys worked for him, and he sponsored 12 boy scout troops.

Some of the Boy Scout troops had marching bands and they probably bought their instruments at a local store called "Rutherford Studios." It was rumored of the Rutherfords that any of them could pick up any musical instrument and be able to play it within a few months.

One auntie secretly wrote poetry.

The news store was inherited by my Uncle Bill, a grumpy man with an eye-patch who lived above the store. Rutherford News closed forever sometime in the late 1970s.

As a child in Scottdale, I would cut up magazines and rebind them in various ways and sell them to neighbors; I also printed a mimeographed science newsletter and tried to draw comics. By the fifth grade I was writing monster plays and staging them in a local garage, and charging admission to the all the neighborhood kids. People in town said I was just like my grandfather.

And here I am, a curmdugeon, publishing books and picking away at writing and music. Did I have any choice in the matter?

This corner building was the site of Rutherford News. Since it was built around 1880, it was probably always in the family.

Fame at Last!

Whoop-de-goddamm-doo! Fox Business Network just sent me an email telling

me that the Poet's Press can have a two-minute spot on the FOX Business

Network for only $4,000. Now I can reach all those toothless

troglodytes who have just been waiting for BIG POETRY ENLIGHTENMENT and I

can sell my books by the boxcar-load. Hell, I'll need my own railroad

siding since Fox Business Network will reach a MASSIVE AUDIENCE of

AFFLUENT CUSTOMERS. Why didn't I think of this before? My god, I can be

famous at last! The Poets Press authors can ride around in limousines!

The Kardashians will quote my poems. My lines will turn up in tattoos,

on T-shirts, and the lids of the flat-brimmed baseball caps.

Thursday, May 4, 2017

The Nosebleed

On a day when the government decides to bolster the prejudicial treatment of anyone who offends anyone's "religion," and a day when the House of Representatives votes to repeal the Affordable Care Act, I am reminded of the time when, as a poor college student, I needed emergency care at St. Vincent Hospital in Erie, PA.

1968

Dizzy and bloodless I am wheeled

into the emergency room. Nosebleed

for hour on hour has left me senseless.

This is a very Catholic hospital.

A nurse with clipboard demands my name.

She looks with scorn at my hair and beads.

“Bet you don’t have no job?” she sneers.

“I’m a student. At Edinboro.”

“Drugs!” she says. “They’re in here

alla time.”

“Nosebleed,” I say.

“I don’t use drugs.”

Nosebleed, she writes,

as I choke on clotted upheave.

“What’s your religion?”

“None.”

“I gotta put something here.”

“Say atheist.”

“Well, that’s a first.

I don’t know how to spell that.”

“A—T—H—E—I—S—T.”

“You could be dyin’ here

an’ you wanna say atheist?”

“You want me to lie on my deathbed?”

She snorts. “I’ll put down Protestant.”

They wheel me in. I’m in and out

of consciousness. Later I wake

in a deserted wardroom. I want to know

how long I’ve been here, how much I lost.

I find the cord and buzzer

that says it will summon a nurse.

I hear a distant bell ringing,

hear voices at the nurses’ station.

Words fly to me like startled birds

“Appendicitis”

“Babies”

“Pneumonia”

then “The hippie in 15-B”

A male voice laughs. “We’ll make up

something special for that one.”

I ring the bell again. No one responds.

I wake again at mid-day.

They wheel in food on a cart.

A plate is put before me—

amorphous meat, a glistening heap

of mashed potatoes, some soggy greens.

I take a spoon of potatoes

wondering real or instant,

bite down on razor shards of glass,

put hand to mouth and see blood streaming.

Rip tube from face spitting rush

for the bathroom

rinse rinse spit rinse

swabbing the blood with a towel

tongue bleeding gums bleeding

dressed myself hastily

left there no one stopped me

walking walking hitch-hiking southward

glad I never swallowed

my special hippie atheist breakfast.

1968

Dizzy and bloodless I am wheeled

into the emergency room. Nosebleed

for hour on hour has left me senseless.

This is a very Catholic hospital.

A nurse with clipboard demands my name.

She looks with scorn at my hair and beads.

“Bet you don’t have no job?” she sneers.

“I’m a student. At Edinboro.”

“Drugs!” she says. “They’re in here

alla time.”

“Nosebleed,” I say.

“I don’t use drugs.”

Nosebleed, she writes,

as I choke on clotted upheave.

“What’s your religion?”

“None.”

“I gotta put something here.”

“Say atheist.”

“Well, that’s a first.

I don’t know how to spell that.”

“A—T—H—E—I—S—T.”

“You could be dyin’ here

an’ you wanna say atheist?”

“You want me to lie on my deathbed?”

She snorts. “I’ll put down Protestant.”

They wheel me in. I’m in and out

of consciousness. Later I wake

in a deserted wardroom. I want to know

how long I’ve been here, how much I lost.

I find the cord and buzzer

that says it will summon a nurse.

I hear a distant bell ringing,

hear voices at the nurses’ station.

Words fly to me like startled birds

“Appendicitis”

“Babies”

“Pneumonia”

then “The hippie in 15-B”

A male voice laughs. “We’ll make up

something special for that one.”

I ring the bell again. No one responds.

I wake again at mid-day.

They wheel in food on a cart.

A plate is put before me—

amorphous meat, a glistening heap

of mashed potatoes, some soggy greens.

I take a spoon of potatoes

wondering real or instant,

bite down on razor shards of glass,

put hand to mouth and see blood streaming.

Rip tube from face spitting rush

for the bathroom

rinse rinse spit rinse

swabbing the blood with a towel

tongue bleeding gums bleeding

dressed myself hastily

left there no one stopped me

walking walking hitch-hiking southward

glad I never swallowed

my special hippie atheist breakfast.

Wednesday, April 19, 2017

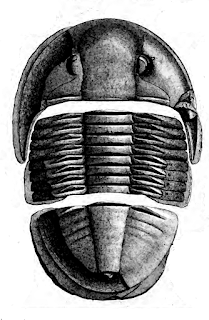

Trilobite Love Song

My thousand eyes are upon you.

Even when I molt, when others would dream

in an agony of pain denial, I stay alert.

I watch for your every passing.

Everything I sense about you

from infrared to ultraviolet

is in perfect focus at every distance.

Not even a feeding cave or a narrow crevice

can hide you from me: I know

the subtle song of your feet and feelers.

The mottled markings on your thorax

make me go rugose: I cannot help it.

The intricate spines of your cranidium,

stretching like the finest sea-flower,

drive me to impolite excesses.

(Oh I have mapped them and would

ten times trace them with my ten

appendages if only you would permit it!)

Even when I molt, when others would dream

in an agony of pain denial, I stay alert.

I watch for your every passing.

Everything I sense about you

from infrared to ultraviolet

is in perfect focus at every distance.

Not even a feeding cave or a narrow crevice

can hide you from me: I know

the subtle song of your feet and feelers.

The mottled markings on your thorax

make me go rugose: I cannot help it.

The intricate spines of your cranidium,

stretching like the finest sea-flower,

drive me to impolite excesses.

(Oh I have mapped them and would

ten times trace them with my ten

appendages if only you would permit it!)

Greater order, you

have never noticed me,

a bottom-feeder for all you know.

Yet I have followed you for years now.

I listened silently as you and all those others

formed into a linked circle, a thousand-feeler,

ten-thousand spine symphony of singing.

I think the earth stopped in its orbit

when you played the click-click-click symphony

of the revered master click-rrr—click---rrr-click---ahk.

All I could so was weep inside my calcite lenses

and let my spines go limp.

have never noticed me,

a bottom-feeder for all you know.

Yet I have followed you for years now.

I listened silently as you and all those others

formed into a linked circle, a thousand-feeler,

ten-thousand spine symphony of singing.

I think the earth stopped in its orbit

when you played the click-click-click symphony

of the revered master click-rrr—click---rrr-click---ahk.

All I could so was weep inside my calcite lenses

and let my spines go limp.

How could you know my dream of you

inspired me to swim higher

beyond the blue-green fringe water

into the blazing Greater Light,

where I lay gasping with salt-dry gills

click-clicking your name

as the Greater Light plummeted

and the blue-white Lesser Light

stole in to replace it —

just so do I, the lesser, pursue you.

inspired me to swim higher

beyond the blue-green fringe water

into the blazing Greater Light,

where I lay gasping with salt-dry gills

click-clicking your name

as the Greater Light plummeted

and the blue-white Lesser Light

stole in to replace it —

just so do I, the lesser, pursue you.

I am not worth

one twitch of your pygidium tail

but I am convinced of a destiny

since ever I first looked upon you.

I guard your molting against all predators,

though you have never known it.

When I was younger, I traced

lewd messages on the sand floor,

wiping them out as fast as I wrote them –

oh, things that would embarrass you,

one typical juvenile verse went something like:

I want to hold my click-click

against your click-click-ack-click

until we grrrr-te-te

one twitch of your pygidium tail

but I am convinced of a destiny

since ever I first looked upon you.

I guard your molting against all predators,

though you have never known it.

When I was younger, I traced

lewd messages on the sand floor,

wiping them out as fast as I wrote them –

oh, things that would embarrass you,

one typical juvenile verse went something like:

I want to hold my click-click

against your click-click-ack-click

until we grrrr-te-te

So as you see, I am not much of a poet,

even less a courtier. My only hope

is that you have held yourself aloof,

that perhaps in your greater essence

is a greater shyness. Or, hope of hopes,

that you have seen me all along,

and only need my boldness. Oh, dare I?

even less a courtier. My only hope

is that you have held yourself aloof,

that perhaps in your greater essence

is a greater shyness. Or, hope of hopes,

that you have seen me all along,

and only need my boldness. Oh, dare I?

Without your prior enrollment and slow

unrolling, without that stretch of feelers

and the ensuing embarement of thorax,

dare I approach and say the words

of surrender and engagement:

unrolling, without that stretch of feelers

and the ensuing embarement of thorax,

dare I approach and say the words

of surrender and engagement:

Thou,

greater than me, and whom I love:

I lay my eggs at your feet.

I lay my eggs at your feet.

Monday, April 17, 2017

Brahms' First String Quartet

For more than ten years, I have been writing program notes for chamber music concerts. I will begin to share these, with a link to a video of a performance of the works. At some point I might have enough notes for a little book. Audiences and musicians have been amused and informed by my notes, so I hope to pass along the pleasure.

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897).

String Quartet in C Minor, Op. 51 No. 1 (1865-1873)

I. Allegro

II. Romanze: Poco Adagio

III. Allegretto

IV. Allegro

Happy was the lot of Louis Spohr, a composer who outlived Beethoven and

composed 36 string quartets. Far less happy was the lot of composers who

trembled under Beethoven’s shadow: Mendelssohn did a youthful quartet fully in

the “manner” of the master’s intimidating last works, but then abandoned that

high and difficult style for a more genial output; Schumann created three

masterful quartets in 1840, and then no more; Schubert capped his quartet

career with masterpieces worthy of his musical hero, but he was dead two years

after Beethoven. Other composers shied away from the genre, and some, like

young Dvorak, were just beginning to find their way. By 1865, Brahms, the most self-conscious of all composers, had composed and torn up twenty quartet attempts. Some were played privately by friends: all were rejected and nearly-all destroyed. This one he kept, and revised, and revised, and revised. By 1873, Brahms had two quartets ready, his Opus 51, the first of which, in the high-stakes key of C Minor, we hear tonight. Brahms was 40 when he published these quartets, and he had still not completed his first symphony, another case of predecessor-panic.

The first movement is a tight-fisted sonata form, with not one note wasted. The two principal themes follow one right upon another. The first theme, although it surges upwards heroically, also has three successive downward leaps, making its return and contrapuntal use easy for any listener to recognize. The second theme, heard immediately after two long-held octave notes on the viola, is more songful, melismatic, chromatic, exactly the kind of theme we will find in his symphonies. The working-out includes sections in sunnier C Major, and then a slide into mysterious C-Sharp Minor. These modulations change the harmonic palette even while Brahms continues his tightly-worked counterplay of themes. One masterful touch in the first movement is that Brahms brings back his second subject, set one pitch higher than the “home key,” so that, although one is hearing a recapitulation of a now-familiar theme, is distinctly different in tone-color (you will hear this after about three bars of distinctly weird pizzicati). The coda is more agitated and shows us that Brahms knows the full weight of writing his first quartet in the “tragic” key of C Minor, although he imitates Bach in having the last note be a broad chord in C Major.

Like Beethoven, whose C Minor “Pathetique” sonata opens out into a melting song in A-Flat, Brahms choose this key for his second movement. This “Romanze” is intimate music, and although the thematic material is based on the main theme of the first movement, this music takes us to a different world altogether. The players are more together than pitted against one another, and we sense a pastoral mood, with suggestions of distant horn-calls. A more meditative middle section, sliding into the minor, hints not just at nature, but nature seen in solitude, but then we are brought back to the “song without words” material from the opening. If the first movement is about nervous nest-building, the second is a celebration of the natural world.

There is no Scherzo for a third movement, as you might expect from a 40-year-old composer still too timid to write his first symphony. Instead we have a moody Allegretto molto moderato e comodo. The key is F Minor (the relative minor of the A-Flat Major key of the preceding movement). The interplay between the violin and the other strings is not so much playful as sinister, and the folkish interlude with odd open-string sounds from the second violin and viola (an effect he had picked up from Haydn’s “Frog” quartet). In mood, I find this one of the loneliest pieces of music in the repertory – not so much a depiction of a lonely character, as music that springs from a solitary nature. If one had to paint this delicate music, I would envision a walk in a November wood, with gray and brown tones predominating. Perhaps, in the middle section, our solitary stroller sees some geese flying overhead, or some ducks nestled along a distant stream. Then, turning his back, he knows he is alone again, and the opening music returns.

In the busy and exciting Finale, Herr Docktor Brahms employs a technique that he would perfect in his symphonies: a short “motto” theme followed by two principal themes. By the time Brahms exposes and unfurls these handsome melodies, full of energy, there is scant time for a big development section, so there is a highly compressed one, followed by the recapitulation of the three ideas, and then a coda. This finale, based on material from the first movement, forms a solid bookend against the assertive first movement.

Brahms is given credit, in his Opus 51 quartets, with re-establishing the genre and encouraging others to go where, previously, only a few hardy souls had tread. We would probably not have the Bartok or Shostakovich quartets, had Brahms not summoned the courage to issue these works. Quartets love to play the Brahms quartets. For listeners with time and intent, it is a revelation to listen to them with score in hand. For the concert hall listener, the rewards may be mixed, as there is a difference, perhaps, between “quartet music” and “music for quartet.” Brahms himself may have sensed that the architecture of absolute music was too complex or dense for the quartet, so he almost immediately made a version of the music for piano four-hands. The outer movements may be daunting, but in the two inner movements, the lyrical gifts and nature-painting instincts of Brahms come to the fore. Or it may simply be that repeated listenings are called for to make the outer movements reveal themselves. Either way, we are grateful to have a time and space to sit quietly, and make it our business to absorb this great work.

Sunday, April 16, 2017

The Waltz in Five-Four Time

We come to the

windows

on rainy nights.

Dogs bay behind

us.

We press our hands

and faces

against the panes.

The waltz beyond

the curtains

lures women and

men

to brazen whirl,

hands so daring

and confident,

slim waists

turning,

strong legs

keeping time.

We hear the beat

but

not the melody,

we see the figures

but

not their visages,

barred by lace and

lock,

senses numbed by

leaded glass,

by the storm

behind us.

Do they know we

are watching?

The servants pass

by,

trays heaped with

wines and sweets.

No one comes to the curtain,

No one comes to the curtain,

no lady, alarmed,

cries out

and points toward

us,

no one observes

our hunchback silhouettes

in

lightning fire.

No carriage came

to take us.

But then, we do

not dance.

We, the beggar’s ragg’d

children,

unchurched half-breeds.

unchurched half-breeds.

They dance to

threes,

we only hear

five/four in thunder time,

lopsided beat of the lame man’s waltz.

lopsided beat of the lame man’s waltz.

A howl! A yelp! The

dogs are coming!

We will be torn to bits if we do not run.

I leave an angry handprint,

tar-black on their white-washed shutter,

before we dash for the darkling moors.

One day we’ll sing at their misfortunes.

One night we’ll dance upon their graves.

We will be torn to bits if we do not run.

I leave an angry handprint,

tar-black on their white-washed shutter,

before we dash for the darkling moors.

One day we’ll sing at their misfortunes.

One night we’ll dance upon their graves.

As You Read This

You think you are

alone.

I watch your hands

flash white

at turn of page,

follow your eyes

from line to line.

Hands do not

blush,

the reading eye

cannot avert,

the mind

does

not suspect

my omnipresence.

Counting the beat

your fingers trace

these

lines.

You even whisper

them

as though my ear

were intimate.

You never suspect

I dream of you,

touch back

your

outreached consciousness.

Concealed amid typography,

sighing in each caesura,

intake of breath at every comma,

Concealed amid typography,

sighing in each caesura,

intake of breath at every comma,

I

am like a boy in the shrubbery,

lover in moonlit garden,

a bare toe jutting

amid the footnotes.

Though you be shy,

lover in moonlit garden,

a bare toe jutting

amid the footnotes.

Though you be shy,

doe-wary

and skittish,

I stalk this poem,

alert

between letters.

Watch all you will

for hawk and hunter,

I am in and on the river

of word-flow.

Casting my net

mid-ship between stanzas

I shall catch you.

Watch all you will

for hawk and hunter,

I am in and on the river

of word-flow.

Casting my net

mid-ship between stanzas

I shall catch you.

Thwarted

Among the ways I have

tried to express it

was the arbor of roses over your door

constructed at night by carpenters,

constructed at night by carpenters,

tip-toed in raccoon

quietude,

pounding felt-covered

hammers and oiled nails--

the roses you snubbed to an icy death

that snowy morning you never looked up,

or back, suitcased to cab for that

solitary European vacation

I helped you plan /

the roses you snubbed to an icy death

that snowy morning you never looked up,

or back, suitcased to cab for that

solitary European vacation

I helped you plan /

Among the ways

were the moonlit

serenatas with mandolins

that elbowed each other behind your fence.

The tenor who labored my verses, your name

he said had too many vowels, the high C

half-voice for the paltry fee I offered.

Yes, the same players who fell from the willows

attempting to get my poems heard

over the tomcat rhapsody

that elbowed each other behind your fence.

The tenor who labored my verses, your name

he said had too many vowels, the high C

half-voice for the paltry fee I offered.

Yes, the same players who fell from the willows

attempting to get my poems heard

over the tomcat rhapsody

and the din of your

air conditioner /

Among the ways

were the commonplace

words, veiled in a blush

that punctuated our

seldom discourse. Not even

“Hello” could be dropped from the tongue single-edged.

Yes, the same words, like “dinner” and “alone” —

“Hello” could be dropped from the tongue single-edged.

Yes, the same words, like “dinner” and “alone” —

(“Just us?” “Yes, the

two of us.” “Get back to you.”) —

that registered blank in your eyes.

the silent phone, the cobwebbed mailbox

say all that need be said /

that registered blank in your eyes.

the silent phone, the cobwebbed mailbox

say all that need be said /

Among the ways

are those men left

over from Fu Manchu

who follow your other admirers about

like dacoits, eyeing the alleys and parapets

for places to make their kill and escape.

Strange how your exes are turning up

dead, or missing/presumed, or reportedly

away with their new enamoratae.

I never planned to spend so much

of my inheritance on hit men /

who follow your other admirers about

like dacoits, eyeing the alleys and parapets

for places to make their kill and escape.

Strange how your exes are turning up

dead, or missing/presumed, or reportedly

away with their new enamoratae.

I never planned to spend so much

of my inheritance on hit men /

Among the ways

are the midnight oaths

and promises

I make to dubious

monarchs of love,

half-seen in the smog of my sulfurous hearth,

as I barter to Eros in Pluto’s coinage

half-seen in the smog of my sulfurous hearth,

as I barter to Eros in Pluto’s coinage

a year of my life, for

a night of yours.

The incense clears,

the brimstone pall

clears out to dawn-light, the mowers

start up at the edge of the graveyard,

clears out to dawn-light, the mowers

start up at the edge of the graveyard,

and no, you are not

there;

you are never there, nor will you be.

Cruel bargain, I am a year more old,

and you a year younger. The gulf

already great between us, becomes a rift,

a continental shelf, extinction crater /

you are never there, nor will you be.

Cruel bargain, I am a year more old,

and you a year younger. The gulf

already great between us, becomes a rift,

a continental shelf, extinction crater /

Be gone, be gone. I am

done with this.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)