BRETT RUTHERFORD’S

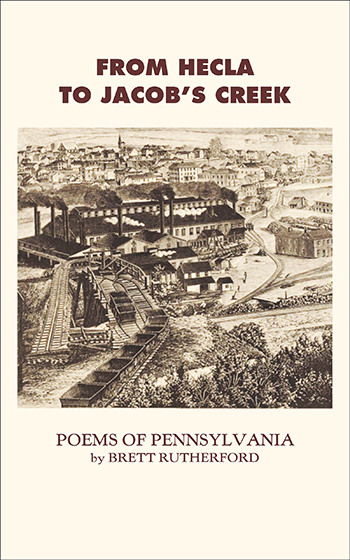

FROM HECLA TO JACOB’S CREEK

American neo-Romantic poet Brett Rutherford spent his first thirteen years in the coal and coke districts of southwestern Pennsylvania. The Rutherfords had emigrated from Northumberland in England to Scottdale around 1880, and took part in its mill-town boom as business owners, financiers, and shop owners. After the Depression destroyed the town’s fortunes, the family remained, a pinch-penny aristocracy. The other side of his family dwells “out home,” where Alsatian maternal grandparents lived in squalor in a tar-paper-covered shack. These country people, their pride and their secrets, left an indelible impression that emerges in this book.

In addition to coke ovens, coal mines, and decrepit houses, the poet’s early childhood is also blasted by the specter of “Dr. Jones,” who, his mother assures him, can be summoned with a phone call, to employ his amputation saws on the limbs of any disobedient child. Connected to this is the threat of “Torrance,” the state mental hospital where several aunts and uncles had been sent, where ordinary mental patients were confined with the criminally insane. The two poems recovering memories of this psychological horror are a jarring specimen of childhood trauma.

This is a book of secrets. A grandmother reveals her Native American origins. An imaginary playmate turns out to be real. A pact is made to help a visiting Rabbi make a Golem. Small boys wrestle with the discovery of a sex manual. A neighbor woman freezes to death in a cold wave. A hesitant girl on the library steps never manages to cross its threshold. After a divorce scandal, the town pulls a blanket of silence and shunning, and a family name is erased from history.

This memoir in poems portrays a true “outsider,” already reading adult literature from the age of six, finding his own way out of a brutal and forbidding landscape.

This is the 316th publication of The Poet’s Press. Published July 2024. Epub and Kindle $1.99. Order from Amazon at https://amzn.to/3WoHuVA.